Henri Poincaré expressed the notion that to create is merely to choose wisely from an existing pool of ideas.

In our previous piece, we deconstructed HR and rebuilt it via macroeconomic principles. Pursuant to the French polymath, Henri Poincaré, we have once again deconstructed HR and have rebuilt it again. This time we are using the building blocks of retail science, more specifically, customer decision making.

Choose wisely from an existing pool of ideas. (Photo: Public Domain)

One of the more exciting building blocks of retail marketing is choice architecture. Let us better (1) understand choice architecture as an obvious yet unforeseen HR tool, and then give (2) proof of concept of how to migrate choice architecture from the retail sciences, where it was born, to the HR profession, where it can thrive.

Choice architecture is a category of design thinking, analyzing how different presentations of identical choices impact consumer decision-making. That’s it! It is one of the most straightforward concepts available to HR. Choice architecture is plugged directly into the motivational sciences and epitomizes the idea of simplicity as the ultimate simplification.

Before we apply choice architecture to HR, let’s roll up the bet by illustrating just how effective and simplistic the concept is.

Choice architecture illustrations demonstrate its sophistication in simplicity.

Do your employees choose the path aligned with shareholder value? (Photo: DepositPhotos)

Design: Public stairs playfully designed as enormous piano keys adjacent to an escalator.

Inducement: Persuade pedestrians, due to its playful approach, to forego the escalator and take the stairs because it’s more fun.

Outcome: Exercise.

How much NYC Taxi riders tip is influenced by the choice architecture of preloaded tip amounts. (Photo: Unsplash)

Design: New York City Taxis now give riders a choice of three different tip options ~ 15%, 20% and 25% ~ instead of having riders input their own tip amount.

Inducement: Studies demonstrate that when three alternatives are available, the middle alternative is usually selected. Subsequently, by replacing the open bucket with a presentation of three predetermined choices for the tip amount, choice overload is diminished which increases the probability that a rider will leave a tip of 20% as opposed to not tipping at all or leaving less than 20%.

Outcome: Increased compensation for drivers. Both the number of riders who leave a tip and the average tip amount left by riders increases. When the law of large numbers is applied, the majority tip amount increases to 20%.

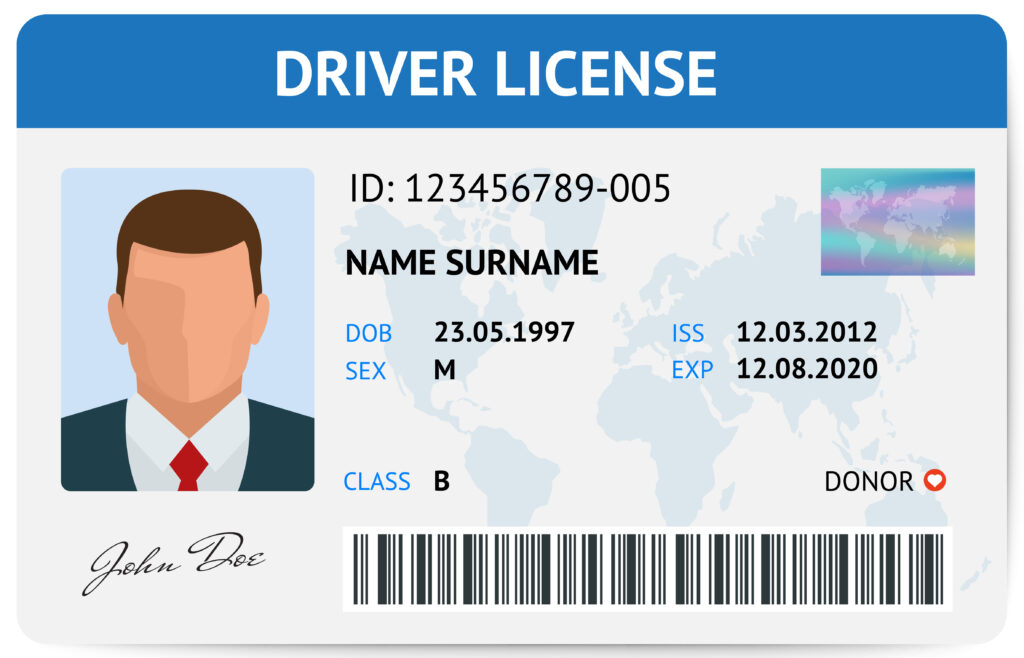

The right choice architecture saves lives. (Photo: DepositPhotos)

Design: Modifying organ donation elections on driver’s licenses from opt-in to opt-out. Opting in is now the default and the de factor choice election if drivers do nothing.

Inducement: Lower barriers for organ donors via default settings that are defined as a preselected choice frame. An extra step is now required for deselection to not be an organ donor. Research demonstrates that consumers are more likely to select default options due to the endowment effect.

Outcome: More lives are saved. Increase donor to recipient ratios, one study concluding by rates twice as high.

Migrating Choice Architecture to HR

The power of our second HR truths comes from its straightforward simplicity, challenging the notion of how typical performance appraisals create obfuscations that run counter to the goals of the organization. While a performance appraisal system can be the most powerful tool a company has to increase shareholder value, often, appraisal systems do not align the interests of the employee with the interest of shareholders. Enlightened self-interest will always win out. When employees are inadvertently incentivized to behave in ways that benefit themselves but run counter to organizational goals, this can be considered a moral hazard.

Choice architecture exists and impacts employee behavior even if HR does not deploy it in its performance appraisals. Consequently, when HR does not consider choice architecture, it is still deploying choice architecture, but most likely deploying the worst version of it.

Choice architecture manifests in (1) which employee goals are measured and (2) how they are measured in a performance review. If performance appraisals use metrics that are not completely aligned with company goals, agency problems, including moral hazards, can occur.

Employee performance must be evaluated by a metric aligned with increasing shareholder value. (Photos: Unsplash)

The universal rule of board of directors and officers of a company is that they have a fiduciary responsibility toward shareholders in acting in their best interests. Why do shareholders purchase stock? What is their interest in doing so? They expect the company to do everything legally and ethically to increase profits as a leading indicator to increasing the share price, so shareholders may maximize their return on investment. This behavior, as per fiduciary responsibilities, is also a legal requirement in the United States.

If employees have a legal fiduciary responsibility to sustain profits and increase share price at a macro level, the metric HR deploys to measure individual employee performance at a micro level on individual performance appraisals must be aligned too. Anything less causes both moral hazards and agency problems.

And yet, we see a plethora of examples where HR operates at cross purpose of their fiduciary responsibility toward shareholders because of how they deploy their choice architecture.

Imagine an HR incentive plan presented to salespeople that has a maximum bonus earning ceiling. Once that ceiling is met, do salespeople continue to book revenue even though HR has stopped incentivizing them to do so? More than likely, the choice architecture shapes their behavior and salespeople will organize their efforts to book revenue the following fiscal year when HR, once again, recognizes their results in remuneration. There are cases where salespeople hit their bonus ceiling in September and simply hold off closing additional deals with their customers until the following January, in order to receive credit for the sale that tallies toward their bonus.

Successful commission and bonus design plans reward employees for acting in their own enlightened self-interest. (Photo: Unsplash)

From the salesperson’s point of view, it makes sense to put the most effort into sales that HR recognizes in their bonus calculations, while spending less effort in gaining sales when it is of no consequence to their compensation. However, from the shareholder’s point of view, for HR to incentivize its own salespeople to stop booking revenue beyond a certain point of the year because a ceiling was reached runs counter to a firm’s fiduciary responsibility. Please stop booking revenue and increase my stock price said no shareholder ever!

This is an example of bad HR choice architecture that causes yet another agency problem between employees and those who hold company stock, including employees who participate in ESPP (Employee Stock Purchase Plans).

HR is the architect of choice architecture. (Photo: Unsplash)

Except for edge conditions, HR, through its choice architecture, owns all company problems. If there is not enough employee behavior that executives deem necessary for success, it is an abdication of HR responsibility to say it is an employee problem. It is an HR problem that can be mitigated by modifying its choice architecture to align with employee enlightened self-interest. How many HR leaders want that level of responsibility? How many CHROs will say they own all a company’s problems, and thus, are responsible to fix it?

Well, at HR Avant-Garde™, we do. Through choice architecture, except for edge conditions, we take ownership of all company problems. Hopefully, those reading this article do as well. Are choice architecture and employee enlightened self-interest really that hard to imagine?

A tale of two HR departments

A school’s HR department has developed a performance appraisal plan for their IT support staff that measures response time to fix classroom PC problems once teachers file a ticket. The pure expression of choice architecture is in the metric HR deploys. In this case, the metric is how many hours from ticket filing to ticket resolution.

You can imagine that IT will come to the classroom and fix the problem rather quickly to minimize classroom disruption time. The quicker the response time, the better the metric that HR uses to judge IT performance that impacts both performance appraisals, promotions and bonus pay.

In this example, HR has decided to only measure response time after problems occur while ignoring performance metrics that measure consecutive days classroom computers are not experiencing problems because of proactive computer maintenance.

But does this common HR practice make sense when proactive behavior is preferable to reactive behavior? No classroom disruptions due to technology fails is a better outcome compared to students losing instruction time because technology fails must be repaired during classroom time. Why would our hypothetical IT staff spend time proactively checking computers and their software prior to classroom start times if HR feels this is not an important enough metric to measure?

Choice architecture tells employees what behaviors are considered vital for organizational success. For employees to ignore choice architecture goes against human nature. It is also an act of second-guessing HR by assuming HR must not be measuring the most important metrics.

HR often evaluates tech support on problem response time. That is the wrong metric! HR Avant-Garde™ advocates rewarding the proactive prevention of problems. (Photos: DepositPhotos, Pixabay)

However, in our hypothetical example, the lagging indicator is not how little classroom time is disrupted while computer issues get resolved during classroom time. The correct lagging indicator is how many consecutive days are classroom computers bereft of any issues because they are resolved proactively prior to class before teachers experience a problem. But if proactive testing is not measured and after the fact response time is, we can be sure that employee energy will flow where HR metrics go.

Employee energy can either go to reactively fixing computers while disrupting the classroom or go to proactive computer maintenance to avoid classroom disruption time. HR’s choice architecture will make the determination.

HR Avant-Garde™ developed the Design-Inducement-Outcome (DIO) model for HR to efficiently operationalize choice architecture.

Model 1:

Design: Performance Review Metric measures response time after classroom computer problems are reported.

Inducement: Quick IT response time after the fact.

Outcome: Classroom disruption time is minimized.

We trust employees to act in their own enlightened self-interest just as companies do. Good choice architecture aligns the interests of both employer and employee. (Photo: DespositPhotos)

Model 2:

Design: Performance Review Metric measure number of consecutive days teachers experience no computer problems.

Inducement: IT resources shift from reactive to proactive, incentivizing IT employees to regularly test computers prior to classroom start times.

Outcome: No classroom disruptions.

An underpinning of the HR Avant-Garde™ approach is predicated on the law of parsimony, deploying solutions with the fewest moving parts for simplicity as the ultimate sophistication.

How do we move from Model 1 to Model 2 in the example above? Simply by tweaking the performance appraisal metrics and measuring the number of tickets opened by teachers because they did experience computer issues. Analogous to how the sport of golf is scored, the lower the number of tickets, the better the performance.

The Italian polymath of the Renaissance would have created a better performance appraisal system than most HR people. (Photo: DepositPhotos)

Now, this is not to suggest that if a ticket is opened, the IT employee did anything wrong, because frankly, all the proactive measurements in the world will not prevent all technology problems. But the theory of large numbers contends that those IT employees that spend more time proactively testing and maintaining computers will statistically experience fewer open tickets over time. The result would be a better classroom experience for the students the IT department serves. It also means their efforts will not go unrecognized.

Choice Architecture Respecting Diversity & Inclusion

Performance appraisals have rated categories that vary across countries, industries and even within competitors of the same industry and geographic location. But many performance appraisal systems are examples of obfuscation when HR’s choice architecture measures employees by leading indicators rather than lagging indicators.

When HR incentivizes leading indicators, it runs counter to the goals of diversity and inclusion because it presumes, despite a plethora of diverse backgrounds, that there is one best way to achieve a goal. However, honoring diversity and inclusion, including diverse cultural approaches to problem-solving, recognizes there are many ways to achieve an end goal (aka lagging indicator) as specified in our model. We have seen performance appraisal categories that evaluate behavior for a sales department. Clearly, revenue is the undisputed lagging indicator for a salesperson and not their behavior. And yet, for all the documented unconscious bias, there are HR departments that, from the limited cultural perspective of their own experiences, still evaluate certain behaviors on their appraisal systems instead of exclusively trusting a diverse workforce to determine the most effective behavior to achieve organizational goals. Measuring lagging indicators exclusively demonstrates that trust and further honors the multiplicity of approaches that comes with diversity and inclusion.

If this is not enough to persuade HR to only measure lagging indicators in a metric-driven format, we can make the clear argument that performance appraisals must be based on bona fide occupational qualifications to ensure legal compliance.

If the goal is booking revenue, the metric is self-evident. Qualitative metrics open the door to bias. (Photo: Unsplash)

The correct lagging indictor would normally quality as a bona fide occupational requirement. If a salesperson must generate one million dollars of revenue as a performance expectation, that is a bona fide occupational requirement. However, if the performance appraisal system measures leading indicators, during any wrongful termination disposition, HR will be required to have all of their statistical correlation data as source documentation to demonstrate that the evaluated leading behavior statistically correlates to the bona fide occupational qualification of, in this illustration, generating revenue.

We have seen salesperson performance appraisal system qualitatively evaluate customer care, relationship building and even personal effectiveness — all vital leading indicators to the lagging indicator of revenue generation. But how could HR objectively evaluate these qualitative leading indicator measurements while remaining in compliance and honoring the diversity of paths to achieving revenue? Customer care, measured in subjectivity, looks at employee behavior instead of the quantitative metric of customer retention rates or retained revenue. Customer care is a qualitative subjective measurement with unconscious bias baked into the cake. A quantitative metric, however, tends to be more objective and is measurable across cultures, countries, and industries.

What is the lagging indicator of customer care? If the intent of customer care is to generate customer referrals or perhaps customer retention, why not measure those metrics directly and trust your employees to calibrate, and even innovate, diverse ways to maximize these objectives?

Quantitative metrics are more objective, especially across cultures and countries. (Photo: Pixabay)

When choice architecture measures employee lagging indicators, we foster creativity that creates an environment for innovation as employees discover the best ways to achieve their goals. The right choice architecture respects diversity as employees, charged with achieving an objective, will strive toward their goal in a way that is consistent with their own culture and values.

Consequently, not only is the right metric vital for good choice architecture, the right metric also transcends cultural bias if it measures a direct bona fide occupational requirement. However, to the detriment of HR, many performance appraisals contain categories that gauge behaviors whose statistical correlation to B.O.R. (Bonafide Occupational Requirements) will always be suspect until HR produces statistical analyses to prove otherwise. It is our experience that most HR departments do not have any regression or statistical models making the case for their leading indicators, which only increases employer liability.

Polymorphous appraisal categories, such as teamwork and interpersonal communication skills are extremely diverse in how these behaviors are exhibited, so by what standard is HR able to benchmark and measure these subjective categories? Appraisals can determine salary increases, promotions and terminations, so the wrong choice architecture using the wrong metric, increases a firm’s liability, especially during a wrongful termination dispute. Using the (1) right choice architecture with the (2) right quantitative lagging indicator (metric) is a fairer approach, with less bias baked into the cake.

Thomas Carlyle may have called economics the dismal science, but today, in this article, we call HR the human science. And there is nothing more endemic to the human condition than choice architecture. It is possible for organizations to simultaneously affect behavior and respect freedom of choice. This makes choice architecture HR’s most powerful truth.

When done well, choice architecture is HR’s most powerful truth. (Image: DepositPhotos)

We offer choice architecture as our second truth because its power is self-evident. Until this article, choice architecture was not discussed as an HR tool, although few would deny its effectiveness when utilized.

The object lesson of our thesis is that choice architecture is designed around how HR incentivizes through the metrics it chooses. However, choosing the optimal metric comes first, even before designing the presentation of choice.

And yet, how many performance appraisal systems are still built around qualitative, subjective assessments, with all the hidden biases that go along with them? Although suspect, even if HR feels these qualitative assessments add shareholder value, where are HR’s statistical regressions to make the case that their qualitative assessments are linked to bona fide occupational requirements?

The Power of Choice Architecture

We conclude our thesis with the ultimate illustration. Just how powerful is choice architecture? The metric that HR deploys to measure employee success in its choice architecture can be stronger and more meaningful than its own company’s mission statement.

The United States Olympic Committee’s mission statement centers on supporting US athletes, while its choice architecture incentivizes earned revenue from its US-based world-class training facilities. Unlike other many countries, because the US does not finance its athletes and most athletes cannot afford Olympic Committee training facilities on their own, according to the Athletes’ Advisory Council’s 2012 study, only 13 percent of US Olympic training center spots were occupied by US athletes. The remaining spots go to train those competing against US athletes, the anthesis of its mission statement! HR is responsible to ensure the choice architecture it deploys in its performance appraisal plans and incentive plans are aligned with the organizational mission statement.

The 60 Minutes sports piece on the US Olympic Training Centers highlights the results of choice architecture misaligned with the organizational goals of supporting US athletics. HR should avoid creating its own agency problem by enabling conflicts between the mission statement it supports and the incentive mechanism that may counter that support. Because the right metric is endemic to good choice architecture, HR could create executive compensation incentive plans based on medals won by US Olympic athletes and forgo any revenue metrics that undermine the organization’s mission statement.

If the mission is to help US athletes win Gold Medals, why are executive rewards based on revenue? (Photo: DepositPhotos)

Alternatively, executive leadership could change the mission statement to include the training of all athletes throughout the world. HR Avant-Garde™ advocates that whatever mission statement stakeholders agree upon, HR should always support it through good choice architecture.

By changing incentives to align with the current mission statement, different behaviors may emerge, including pressure on the government to better subsidize athletes or even more fundraising to cover the costs for training at US Olympic facilities. Employees perceive the metric HR decides to measure in its appraisal systems as a gauge to intuitively understand what behaviors HR deems important to the organization. So, we can simply change the choice architecture from revenue to medal count to align appraisal-incentive systems with the mission statement — or stakeholders can change the mission statement. The object lesson is that HR’s choice architecture should be aligned with the organization’s mission statement.

Your shareholders don’t win when employees are incentivized to lose. (Photo: Pixabay)

Ineffective choice architecture was arguably on display during the Badminton games of the 2012 London Olympics. Athletes from three countries were accused of intentionally missing Badminton shots during non-final elimination rounds just to win a gold medal. Let that sink in. The BWF accused three teams of intentionally trying to lose games just to increase their chances of winning a gold medal.

Now, who would argue that winning a gold medal is not an optimal metric? But the choice architecture created an incentive to lose certain games in non-elimination rounds because the losing team would secure a more favorable position in the next round by playing less competitive teams. Perhaps the games’ choice architecture could be redesigned to remove the incentive to lose games in non-elimination rounds by allowing the winning team to choose its next competitor from the winners of other non-elimination rounds? Notwithstanding, when losing a game is desirable because it increases the chances of winning a medal, we are viewing choice architecture run amok followed by the law of unintended consequences.

With good choice architecture, US Olympic Centers will align with their mission statement. (Photo: Pixabay)

We love the Olympics and only use them as examples to inspire HR to consider its own choice architecture when designing appraisal systems. We deliberately included non-HR examples in this HR article to demonstrate how prevalent choice architecture is in our lives and how often it appears as something beyond our control. But it is not.

Upon two concepts, (1) choice architecture and (2) enlightened self-interest, HR owns most of a company’s problems. If HR is not witnessing the behaviors it links to organizational success, HR may be using a bad metric.

A January 2020 New York Times article illustrates the intersection of bad choice architecture and inadequate workforce planning. Pharmacists complained that because the quantity of filled drug prescriptions was a metric they were evaluated on, the push to do more with less was resulting in errors that caused patients to receive the wrong medication. Imagine a different choice architecture, though, that instead only measured quality of service and not the quantity of service? Would that influence different behaviors in employees? Yes, it would!

Incentivize employees to make the right moves for themselves and the company. (Photo: DepositPhotos)

Changing a company’s choice architecture is as straightforward as choosing a different metric on an employee appraisal form. So, the real challenge is to change HR’s mindset and to remind the profession of the power of its architecture as an HR tool to increase shareholder value and drive ethical behavior. Choice architecture as an HR tool combined with HR’s ownership of appraisal systems and incentive plans means that HR owns all company problems.

Do we really want to take ownership of all company problems? Yes, we do, because we are HR. We love our employees and we love our companies, and we never address a problem without also addressing the solution.

If you still need more convincing about the sheer power of choice architecture, ask yourself if a turkey in America would vote for Thanksgiving?

The least you need to know:

1. Choice architecture shapes employee behavior.

2. HR is the architect of choice architecture.

3. Choice architecture manifests through incentive plans & metrics used in employee appraisal systems.

Vincent Suppa works with startups and investors and teaches graduate courses at New York University. His email is vs54@nyu.edu.

© Vincent Suppa 2021